Dresden Illuminated Manuscript of the Sachsenspiegel

For conservational reasons, the original of the Dresdner picture manuscript of the Saxon mirror can be exhibited only at longer intervals in the treasure chamber of the book museum. The respective presentation time will be announced in time.

A digital presentation of the Sachsenspiegel can be viewed at the SLUB Digital Collections at any time.

Eike von Repgow’s Book of Law

According to the preamble to the Sachsenspiegel we know that Graf Hoyer von Falkenstein (1211-1250) commissioned Eike von Repgow to compile this legal document:

Nun danket al gemene

Deme van Valkenstene,

De greve Hoier is genant,

dat an dudisch is gewant

Dit buk dorch sine bede:

Eike van Repchove is dede.

Nun dankt alle zusammen

dem Herrn von Falkenstein,

der Graf Hoyer genannt wird,

dass dies Buch auf seine Bitte in

deutscher Sprache abgefasst worden ist.

Eike von Repgow hat es getan.

Eike von Repgow (from Reppichau near Dessau) first transcribed “das Sassen Recht” into Latin, and then translated the legal code into German.

There are only six documents which provide information about his life; as far as can be discerned from these documents, he must have lived between 1180 and 1235.

It remains unclear whether or not von Repgow wrote the Sachsenspiegel at the Burg Falkenstein in the eastern foothills of the Harz mountains.

Contents

The Sachsenspiegel consists of three parts: the preambles, the section detailing common law, and that defining feudal law. The preface mentions that the source of this legal code is divine order: God is himself the Law. The author requests the support of "righteous people" in the case of having overlooked any legal questions, asking them to settle such matters in accordance with their "insight" to the best of their abilities.

The section describing common law contains three books, which are divided into 71, 72 and 91 articles respectively.

Feudal law is delineated in 78 consecutive articles, with no further subdivisions.

The following legal areas are covered:

- Constitutional law

- Constitution of the courts

- Lehnrecht

- Criminal law and criminal procedure

- Family and estate law

- Village law, personal and property law

History

It was most likely the interference of foreign laws (Roman, canon law, Lombardic law) that led to the creation of this domestic common law. As a legal counsel, Eike von Repgow hoped to make a significant contribution to the possibility of peace, given the conflicts of the time between the Staufer and the Welf dynasties, between the emperor and the pope, as well as those having to do with the colonization of the area east of the Elbe.

The first version was written between 1220 and 1235. The Latin document has not survived.

The version of the Sachsenspiegel that is known today evolved over approximately two centuries. The text underwent many changes in light of its intensive use and long period of validity. By comparing the ca. 460 surviving manuscripts (and fragments), it has been possible to discern various developmental stages of the text and text classes (see H. Lück: Sachsenspiegel, p. 24).

The oldest existing Sachsenspiegel manuscript (from ca. 1300) dates from the Quedlinburg Stifts- and Gymnasialbibliothek (abbey and school library) and is preserved in the state library in Halle an der Saale.

Impact on Europe

The Sachsenspiegel served as a model for numerous other books of law (e.g., Augsburger Sachsenspiegel, Deutschenspiegel, Schwabenspiegel). Along with the Magdeburg town laws, the Sachsenspiegel had a far-reaching effect, reaching Eastern Europe (reaching the area of Krakau, Lviv, Kiev, Minsk, Vilnius, Riga, Reval, Toruń). Numerous Polish language versions were published in the 16th century.

In the kingdom of Prussia, the Sachsenspiegel was used until the introduction of the Allgemeine Landrecht in 1794. In Saxony, the Saxon Civil Code (Sächsisches Gesetzbuch Bürgerliches) replaced the Sachsenspiegel in 1863. However, in Anhalt and Thuringia, it was not replaced until 1900, when the German Civil Code was introduced (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch für das Deutsche Reich), which is still in use today.

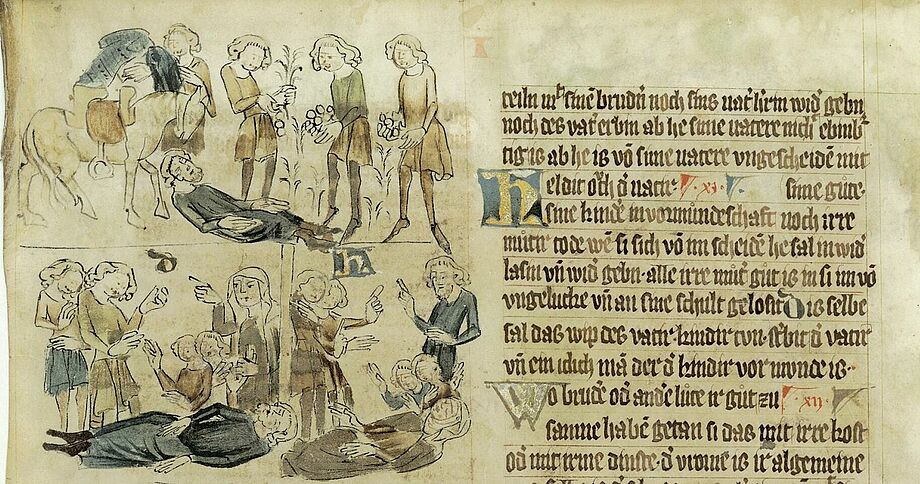

Four Illuminated Manuscripts

The most beautiful copies of the Sachsenspiegel are four illuminated manuscripts held in Heidelberg, Oldenburg, Dresden and Wolfenbüttel, which were produced between 1300 and 1371. Although each of these codices is stylistically distinct in stile, they all share a characteristic and unique combination of image and text. The content of each page is arranged into separate columns for image and text, which enhance and clarify each other, and which are linked by decorated initials.

The Heidelberg Illluminated Manuscript:

This is the oldest, but also least complete of the codices, with 310 image sequences on 30 (of the original 92) pages. It originated around 1300 in Upper Saxony. As part of the Heidelberg Bibliotheca Palatina, it was taken to the Vatican, but returned to Heidelberg in 1816.

Image decriptions

The Oldenburg Illuminated Manuscript:

This manuscript contains the most complete text. It was commissioned in 1336 and illustrated by a monk from the Rastede monastery near Oldenburg. Only a few of the 578 image sequences on the 136 pages were painted in. This manuscript was acquired in 1991 with the support of the Niedersächsische Sparkassenstiftung, and is housed at the State Library of Oldenburg.

The Dresden Illuminated Manuscript:

Dresden’s manuscript originated between 1343 and 1363 in the area of Meißen. Its 924 image sequences on 92 pages are not only the most extensive remaining scenes, but are considered to be the most artistically valuable. This manuscript has been in the Dresden Electoral Library since the time of Augustus, Elector of Saxony (1553-1586).

The Wolfenbüttel Illuminated Manuscript:

a more recent sister manuscript to (copy of?) the Dresden manuscript, this codex originated between 1348 and 1371, and contains 776 image sequences on 86 pages. It was acquired for the Wolfenbüttel Library in 1651 by Duke Augustus II of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1579-1666), the godchild of Elector August of Saxony.

Sachsenspiegel online (commented presentation)

The Dresden Illuminated Manuscript

The Dresden Illuminated Manuscript was kept in the collections of the Electoral Library, later Royal Public Library of Dresden in the castle, then in the Zwinger, and after 1786 in the Japanese Palace.

After the destruction of 1945, the library was moved in 1947 into former army barracks in the Albertstadt in the northern end of Dresden.

Due to extensive damage to the manuscript, the original remained mostly unavailable for research. Since the facsimile of the Wolfenbüttel Manuscript was made public, the research community has begun to show renewed interest in the Dresden Manuscript.

As early as 1902, the Munich scholar Karl von Amira issued a facsimile on behalf of the Royal Saxon Historical Society. 187 monochrome pages and 6 "double collotype prints" were printed using "orthochromatic imagery" to create the reproduction. This pioneering achievement led Amira to publish a two-volume commentary, which has yet to be replaced by an updated text and commentary volume.

Restoration Efforts

During the bombings of Dresden on the 13th-14th of February and the 2nd of March 1945, the Japanese Palace was destroyed, and the Saxon State Library’s collection suffered great losses and damage. The precious manuscripts were taken to a basement bombproof shelter, which was unfortunately flooded by seepage, extinguishing efforts, and floodwaters from the Elbe.

In 1989, funding from the Niedersächsische Sparkassenstiftung made it possible to restore the Sachsenspiegel in the Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel. Chief Conservator Dag-Ernst Petersen, in a collaborative effort with the Clausthal-Zellerfeld University and the University of Applied Sciences in Cologne, began work on the manuscript in 1991, identifying the pigments and writing instruments used in its creation. Stains and spots of transferred ink were removed, gold and silver gilded areas were repaired. After lengthy preparation, the most difficult task was achieved: the hard and warped parchment pages were smoothed out, using a special humidity-controlled chamber.

Although the restoration was not able to recover colors that had been lost, the high-quality ink drawings are now visible and for the most part in excellent condition.

Facsimiles and Commentary Volumes

Already in 1902 the Munich scholar Karl von Amira published a facsimile on behalf of the Royal Saxon Commission for History. 187 pages were reproduced in one colour and 6 in colour by "double light printing after orthochromatic photographs". This pioneering work was followed in 1925-1926 by a two-part commentary volume, in which, among other things, the colours of each page are mentioned.

Before the manuscript was rebound after restoration in Wolfenbüttel in 1999, all pages of the manuscript were digitized. On this basis, a facsimile was produced by the Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt Graz (ADEVA) with financial support from the Free State of Saxony, the "Deutscher Sparkassen- und Giroverband" and the "Ostdeutsche Sparkassenstiftung im Freistaat Sachsen", and was presented in Dresden on 20 March 2002.

In 2006, under the editorship of Heiner Lück, Professor of Civil Law, European, German and Saxon Legal History at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg and member of the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig, a text volume with transcription, translation and commentary on the pictures followed in 2006 and an essay volume in 2011.

Since 2008 the manuscript has been accessible in the Digital Collections of the SLUB.

Within the framework of the project „Tiefenerschließung und Digitalisierung der deutschsprachigen mittelalterlichen Handschriften der Sächsischen Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden“ (2008-2016), funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), the manuscript was re-described according to current standards.